Sara Tas: Plein air painting was a nineteenth-century development that allowed the artist to leave his/her studio and – thanks to the invention of the paint tube – paint direct impressions of nature even in nature itself. In works like Ottenstein you seem to take this concept to its extremes [not painting in nature but letting nature itself work on the canvas]. Does your work indeed relate to this art-historical tradition?

David Roth: I think my approach to art is often a tandem of seriousness combined with childlike playfulness, humour and the questioning of set rules. My projects in nature are a constant interplay of serious and comical endeavour. Plein Air painting happens - as the name suggests – in the open air, outdoors with natural light conditions. Plein Air brings to my mind stories about artists like Turner, Munch or Van Gogh: William Turner who had himself tied to a ship’s mast, to immerse himself into the experience of a storm on the open sea in the most immediate way before painting ‘Snow Storm - Steam Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth’ in 1842, Edvard Munch who deliberately left some of his paintings in the open, stating ‘It does them good to fend for themselves’, Vincent Van Gogh, who wandered the countryside with his easel, completing his paintings in the open air in any wind and weather or rather despite the weather. Bold and absurd at the same time.

ST: By taking the canvas outside and literally dragging it through nature, you allow a painting to emerge as a ’natural product‘. In this way, are you also trying to question, or perhaps even eliminate, the role of the artist? At the same time, you turn the artist into a performer, is it still about painting?

DR: The Austrian art theorist Andreas Spiegl, who I am very fond of, wrote about my work ‘Ottenstein‘ (2022): “Pictures can be painted, displayed, or hung on a wall and one can live with them to pursue a view of the world”. All the projects with canvases in nature I have made since 2009 are very much about partnering up with the canvas, going on journeys and adventures and letting things take their course.

I like to quote a good old friend of mine by the name of Vincent Van Gogh, who said in one of his letters to his brother Theo: “And I believe the public will begin to say, deliver us from artistic combinations, give us back the simple field’. * That sounds almost like an invitation to do what I do when I go on field trips with my canvases.

I understand the strict demarcations of different art movements and genres in the time in which they emerged, as a means of positioning themselves and I do not condemn that. My idea of art, however, does not mean I decide on a certain medium and understand the (once) set rules and boundaries as immovable. I am doing things with paint. I am doing things with painting. I am doing things with paintings. The root of my interest has always been and still is painting, but I reserve the possibility of expressing myself in other media through painting. Indeed, the act of painting always has a performative side even in the classical sense. When attempting to name something, it seems convenient and easier to categorise (it). But just as humans don‘t only show one nature in different situations and with different opposites, each art form also can be erratic, thus rendering precise categorisation impossible, especially when boundaries are blurred.

Questions and ideas such as ‘What is painting?‘, ‘How does a canvas become a painting?‘, ‘What can a painting be?’, ‘Painting as artefact of an adventure‘, delineations of different media, genres and art movements that grow indistinct, the experience gained by spending

time with the canvas and seeing paint, material and external influences such as nature and weather as partners in the creation of a painting, have manifested themselves in me during years of making.

ST: Ottenstein? Why is this work called Ottenstein?

DR: Ottenstein is the name of a large lake as well as the Lower Austrian area surrounding it.

I had been toying with the idea of turning a canvas into a raft and sail for a long time, but kept postponing it. When in 2022 I was ready to give it a go, Ottenstein sprang to mind instantly. Ottenstein is a place that is actually very dear to me. Already as a child I used to go fishing there with my father every summer. We rented a small wooden fishing boat and stayed on the water from very early in the morning, sometimes even before sunrise until late into the night to fish and be in nature.

The day I set out for the Ottenstein project was rainy and very windy in the beginning, but soon calmed down while I hiked through meadows and forests by the lake for hours, dragging two canvasses behind me like a farmer would his harrow, very close to nature, that imprinted itself on the canvases.

Later I transformed the two canvases into a raft, gliding over the water steered by the wind. I expected I would be on the water only for a few minutes, but the raft kept dancing on the water for hours. Night fell and it was pitch-dark, only the raft’s canvases were glowing. The light the photoluminescent paint I had used to prime the canvases emitted, attracted fish and I could feel them touching the raft’s underside. By attaching the sail, the second canvas, to the other canvas, I had ruled out having any control over the direction the wind might make the raft take. I was a tourist and a passenger in my own project.

Back on the shore, the two canvases’ transformation made further progress: from a raft into a tent providing a place to sleep.

ST: In Ottenstein you don‘t paint a landscape but have the landscape ‘paint’ itself, in your Flower Paintings you don‘t paint flowers but make the flowers paint. Is this inversion a way for you to get to the essence?

DR: Using a motif not only as such but (also) as a painting tool is a very direct way of depiction - the motif ‘paints itself ‘ and I am responsible for the path we take. So, who is the author? I would call it a co-operation between me and the landscape or me and the bouquet of flowers in relation to the respective external situation that has an impact on the process or on our common path. The traces on the canvas, caused by the motif, the landscape, the bouquet of flowers itself painting the motif, the movement, any changes of direction and the path are directed by me or circumstances during the act of making. For me, there is something very primeval about it, which I find refreshing because it brings a certain lightness contrasting the ‘serious‘ references every painterly gesture carries.

ST: How do you choose your flowers for the Flower Paintings?

DR: It depends on the time of year and where I am, when I do Flower Paintings. The flowers in the current series are all wild flowers - either from the French or the Austrian countryside or from places a few minutes away from my studio in Vienna, near train and subway stations or abandoned construction sites. Ultimately, everything is about selective attention, about being aware of things that have been there all along but went unnoticed. It took me years to realise there is a wide variety of wild flowers close to my studio.

ST: The Mud Paintings are made from nature for nature and you exhibited them in their natural environment, the forest. Are your Mud Paintings meant to last or to fade away

eventually? Can you give me an example of what you hope they mean or could mean to any animal encountering these works in their natural habitat?

DR: The urge of documenting something and leaving it behind in caves or in nature arose already at a time when nature was not a place of recreation but human habitat. At a time when art was made without the concept of art even existing. At a time when any artistic gesture took place without reference to previous art.

I assume the concept of art as we understand it today is intangible for animals. The question of what my mud-painted canvases represent for animals was not the motivation behind exhibiting them in the forest, though the idea, that they create an artefact capturing this moment in time of a human being and nature communicating, appealed to me. I created the Mud Paintings in the forest and exposed them to the weather for eight months where they became part of the environment. Now I am interested in displaying their status quo indoors.

ST: How are the works you named ‘Brain’ constructed? Do you deliberately work on one installation and is each layer a continuation of the previous one? Or is it instead an accidental, random, organic accumulation developing over a longer period of time that says something about your work process in general and the wanderings of your mind?

DR: The ‘Brains‘ are trestles piled high with painting. I build them from old stretcher frames. The body of a ‘Brain‘ is made from layers and layers of material, which can be canvasses and paintings cut from their frame, joined by pieces of fabric I used as a palette, a rag employed to clean brushes, scraps of canvas to test the quality of colour, a section of a painting I cut out because it did not work composition-wise, plastic foil that served as a palette or to protect the floor, terry cloth towels used to clean paint pots or the studio floor. Some of the material is produced as part of so-called menial preparatory or painterly tasks or generated as a by- product in the painting process. I see this kind of painting as the purest form of painting - albeit a form of painting that does not claim to be painting in the process of creation. This provokes a painterly freedom and lightness difficult or even impossible to achieve consciously. Layer upon layer on different trestles from different painting projects from entirely different periods of time and work.

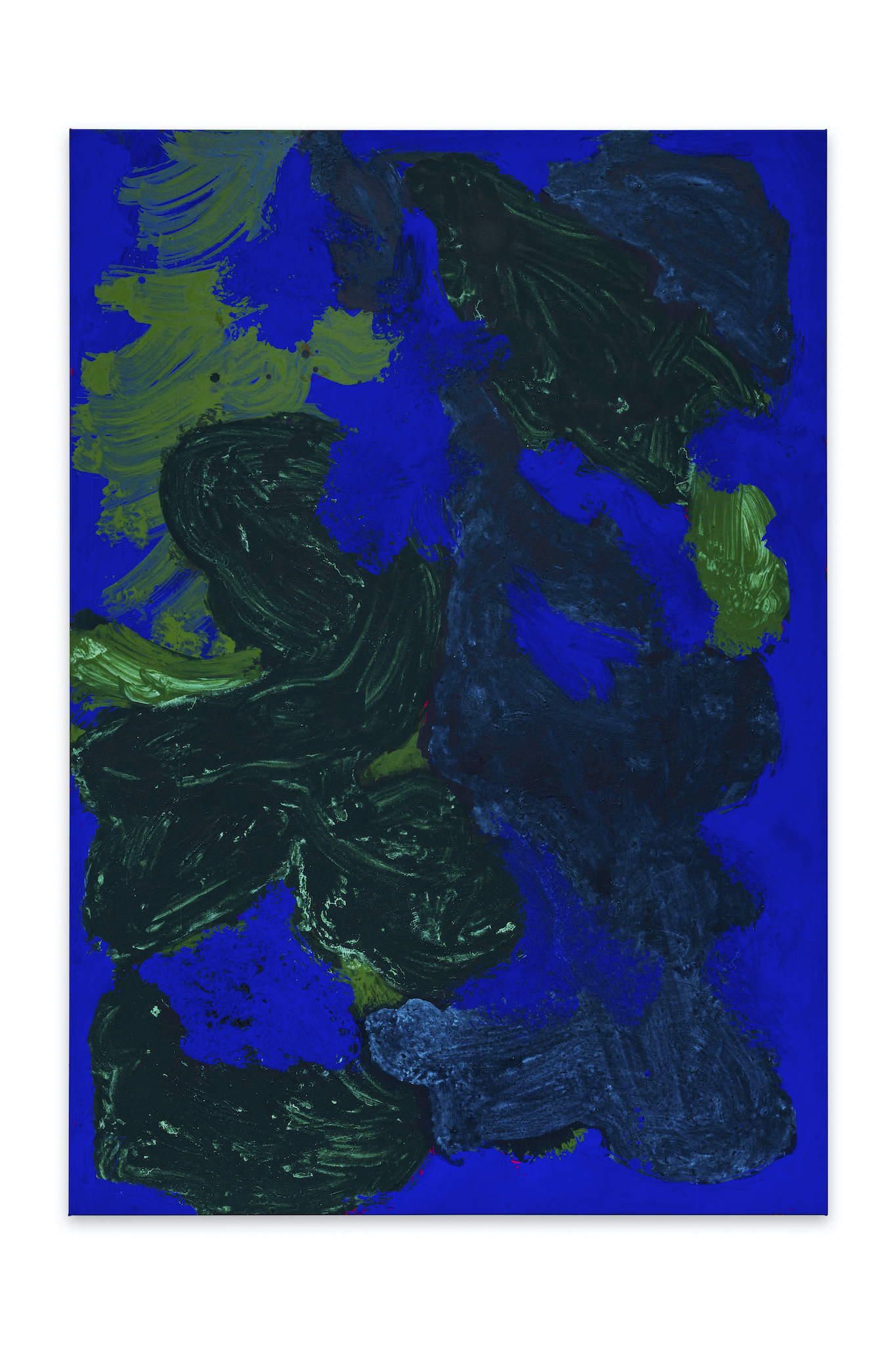

ST: You indicate that the ‘Painting Painting’ paintings are primarily about spontaneity and playfulness. Does this mean you also associate them with COBRA or Action Painting, or are you more concerned with letting go of these art-historical associations and being as free as possible as a painter?

DR: My ‘Painting Painting‘ paintings are created by over-painting again and again over a long period of time. A canvas becomes a palette becomes a painting - and the painting turns palette again in a rhythm going on for years and years. Usually, after each painted layer, weeks, sometimes months go by until the surface of the oil paint is dry and the next layer will follow. Over the years, colour accumulates on the canvas in an almost sculptural manner, sometimes even extending beyond the edges. It is a playful and spontaneous approach to painting. Ultimately, art history will make its voice heard anyway and painterly vocabularies from different periods, movements and genres meet, that may never have had any temporal or formal relationship.

_

Sara Tas is associate curator at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

*Letter 291, Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, between 4 and 9 December 1882. vangoghletters.org

Certain circumstances. Selected flowers. A solo exhibition by David Roth27/11/2024 - 07/02/2025Panis77 rue Jeanne d'Arc, Rouen (fr)

Certain circumstances. Selected flowers. A solo exhibition by David Roth27/11/2024 - 07/02/2025Panis77 rue Jeanne d'Arc, Rouen (fr)